The Latest News

What's Happening...Donate to the Society's

Annual Appeal using the Donate button below. Thank you for your support! Recent Zoom Programs

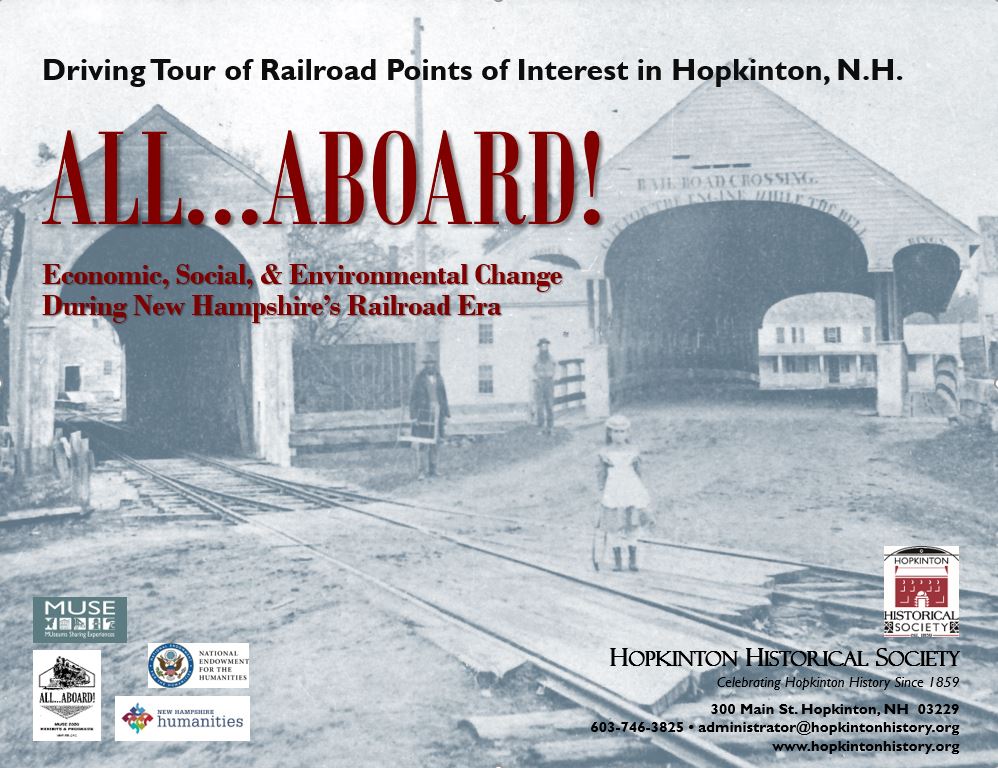

Railroad Driving Tour

Hopkinton Historical Society Hours

From April through December, Hopkinton Historical Society is open on Thursdays and Fridays from 9-4, and Saturdays from 9-1. From January through March, the Society is open on Thursdays and Fridays from 9-4, We look forward to seeing you! About Us

|

To register, go to: https://www.zeffy.com/ticketing/d918befd-2e47-4e6a-967d-bd519e32d71b

Pandemic Stories

One hundred years from now, what would you like people to know about the COVID-19 Pandemic? Hopkinton Historical Society would like to document people’s stories of what they are feeling, seeing, and/or doing during these continuing, unprecedented times. Now that several years have passed, how have things changed? What are your fears? What things do you miss from pre-Covid? Email your pandemic stories and photos to [email protected]. Below is a submission from Lucas Lajeunesse, who lived in Contoocook from 2013-2020, when he moved to British Columbia to attend school.

Graduating from Hopkinton High School in 2020

Lucas Lajeunesse, February 3, 2024 I saw on your page [website] that you are looking for stories from the COVID pandemic. I was in my senior year of high school when it started to become a thing in the news, around mid to early January. It was eclipsed by Trump’s killing of the commander of the Iranian revolutionary quads forces in Iraq and the potential war that was unfolding. It was then a TikTok/internet scare when it was spreading in China. I remember expressing concern about its potential for becoming a pandemic when Wuhan locked down on January 23rd and a class mate making a racist remark about how the Chinese were dirty people and it would stay over there (this is summed up in a kinder way than it was said). The students and teachers didn’t talk much about it in February. I remember when Bologna in Italy was being hit in mid-February and the rapid spread/prevention measures happening in Italy. I remember realizing that when it was spreading in Iran around the same time there was probably going to be a pandemic. The last event I experienced before the pandemic was the high school winter carnival. It was in late February and to anyone watching the pandemic unfold it was obvious it was a pandemic and it would come to New Hampshire. However, the winter carnival went on, to me there was a weird sense of the calm before the storm. To many, COVID was a trend in January and they didn’t care about it then. In one week in March the whole attitude of the school turned upside down. On Monday I remember telling my math teacher that school was gonna be canceled in two weeks and we weren’t gonna come back. He scoffed at this notion and said at worst we’ll have two weeks off. Many people thought at the start of the lockdowns it would only be two weeks but just as many say “the war will be over by Christmas,” it never is. For the students it was like a nasty rumor. We were all talking about it, especially after the NBA shutdown, cases in NYC were on the rise and Tom Hanks tested positive. I was paranoid that week any time I saw a sick student go to the nurse. I contemplated wearing a mask to school. By Friday it was all anyone could talk about. Our classes that Friday were discussions on what was happening and what might happen. Everyone now had their own opinions and some discussions turned into arguments over how long we’d be out of school. It was a running joke that day that is was our last day of school. That Friday (ironically enough I think it was March 13th, Friday the 13th) is burnt into my memory. It’s one of the moments where I felt the weight of global events on my shoulders, I felt caught up in it. The whole day I was on edge thinking “this is really it, I’m living through the start of a pandemic, it has arrived.” That was the class of 2020’s last day of school. Waving goodbye as a joke to people but knowing this really could be goodbye set in at the end of the day. I remember one girl crying about that when I was walking out the door from high school for the last time. We went into lockdown and I was surprised at how relaxed some things were. I think because I had seen the responses in China and Italy/Europe I was expecting way more but I found it to be relaxed. There was nasty panic buying at all the grocery stores and the shelves were pretty empty. I did all the grocery shopping in my family and that’s when I started to wear a mask. It took two weeks for the school to start online. I didn’t even try, I’d log in, go back to sleep, play video games, go log into another class, meet my buddy in his back yard and practice archery, sign out. Around mid-April I fell sick myself. To this day it is the sickest I have ever been. I had chills, sweats, high fever, a deep cough, body aches and intense bouts of fatigue. My mom insisted that I wake up for school still, one of my memories from being sick with COVID was being awoken from the most intense fever dream of my life and being told to login to school, then going onto YouTube and telling my mom I was on my school page. I wasn’t worried about her seeing my screen because she was too scared to enter my room. Toward the end of my time being sick I got a COVID test by the national guard. It was the first dystopian moment for me, when it had been going on long enough that the initial shock was gone and now we are living with it. I think at some point in May we were allowed back into the school for a couple of minutes to grab everything from our lockers. We were met by masked teachers one by one and sent in to grab everything. My older siblings had graduated from high school in previous years and I remember their walk through the school. For me this graduation walk was done in a poorly lit empty school while wearing a mask and being herded around. I was in there for maybe 5 minutes and I haven’t stepped foot in the high school since. My graduation was the most dystopian event of my life. It is the only other time I truly felt the weight of global events on my shoulders. I went with my parents and we were told to wait until our group was called. I went with a handful of kids from my grade to our 6 by 6 social distance squares. They were in the outfield of the baseball field. There was an orange plastic fence surrounding the area so people wouldn’t come in. In the front was a stage. I talked to a handful of people close by, but we were all in masks. They were matching masks hand made by Mrs. Thornley, the 8th grade math teacher.* I remember one family refused to wear the masks given them and the fuss that created. When they called my name, my dad handed me my diploma. When I hugged him and my mom I remember my masked slipped up and I was quick to put it back on. This is the last time I saw almost all of the people I went to high school with. I spent 6 years with them and knew so many of them really well. In such a small setting you get to spend so much time with your classmates. I grew so much as a person in front of them and vice versa. To see so many of them for the last time in a field socially distanced wearing masks is kinda haunting. It was a surreal way to be sent off into adulthood. There was a photo session afterwards that the parents had gotten together at Houston fields. Some parent was saying “they can’t get us there” should have taken the hint. We went and many people were maskless in a big group. It’s a funny thing to say now but in the moment for me it was like what the f***. I was one of a few who kept my mask on for the photos. My dad stayed in the car and my mom started out cool about it but by the end was freaking out. It seemed like everyone wanted to ignore COVID, forget about it even while we were still in the thick of it. I was very worried about that in the moment, that people wanted to ignore what was happening in front of their very eyes. But now that it’s over and 4 years have passed I still have the same fear. COVID turned out to be the deadliest event of American history yet we all want to forget about it. I fear that we will and we won’t learn any lessons about ourselves, about misinformation, fear and mass death. As someone whose entire adult life so far has been dominated by COVID, I think it is very important that we recognize and reconcile how impactful and damaging this all was. I hope we don’t forget about COVID like we forgot about the 1918 flu pandemic. I hope that stories about COVID are told and retold so we, as a society, can address these wounds that were cut into us. If we don’t I fear this spiral of hatred, misinformation, ignorance, misunderstanding, and apathy will only get worse. * Following publication of this piece in Susan Covert's daily email, "Hopkinton News," we received additional information about the masks: The Hawks 2020 mask featured in yesterday’s Hopkinton Historical Society’s piece about the Covid epidemic, was designed, but not made by, Melanie Thornley. Michele Allen, whose child was in the 2020 graduating class, sewed the masks for graduation. A seamstress, she volunteered her time and bought the materials. In all, Michele made nearly 300 masks. Each graduate received three masks and masks were provided to all teachers and administrators attending graduation. Michele also sewed masks for the 2021 graduation; Project Graduation paid for the materials. Image of Hopkinton High School graduation on June 13, 2020 taken by Bob LaPree. Hopkinton Historical Society Releases “ALL…ABOARD!”

Driving Tour of Railroad Points of Interest in Hopkinton, N.H. Looking for something to do from the comfort of your car or couch? Want to learn more about the impact the railroad had on the town of Hopkinton? If so, please take a look at Hopkinton Historical Society’s “ALL…ABOARD!”, a driving tour of railroad points of interest in Hopkinton, N.H. In March 2020, Hopkinton Historical Society was in the middle of planning its summer exhibit, as part of a 16-member collaboration (MUseums Sharing Experiences, or MUSE) that had organized eight exhibits and more than 30 programs on the economic, social, and environmental impact of the railroad in New Hampshire. When the pandemic forced the closing of the Society, we knew we still wanted to move forward somehow with our summer exhibit. Given the continued uncertainty regarding opening dates and people’s comfort levels with gathering in groups indoors, we decided the best approach was to take our exhibit on the road! Specifically, to put together a driving tour that can be viewed or downloaded from our website, or followed on Clio, a downloadable app that allows you to view driving tours of historical and cultural sites. Clio can be accessed via its website or on a mobile device. The tour includes seven stops in Hopkinton and Contoocook. In addition to physical landmarks, the tour examines how the railroad expanded markets for farmers, increased tourism, expanded mobility for rural communities, and impacted mills and factories along the Contoocook River. However, not all of the changes brought about by the railroad were positive. Information about immigrant laborers, those displaced from their homes along the river, and the townspeople and other investors who purchased bonds that paid for the railroad is also included in the driving tour. We hope you enjoy the driving tour. If you have images or stories you would like to share, please contact us at 603-746-3825, [email protected], or www.HopkintonHistory.org. This project was made possible with support from New Hampshire Humanities, in partnership with the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Hopkinton Historical Society

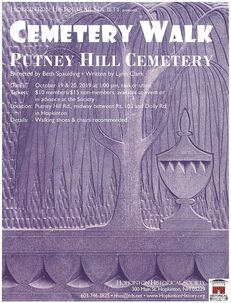

Receives National History Award The American Association for State and Local History (AASLH) proudly announces that the Hopkinton Historical Society is the recipient of an Award of Excellence for the 2019 Putney Hill Cemetery Walk. The AASLH Leadership in History Awards, now in its 75th year, is the most prestigious recognition for achievement in the preservation and interpretation of state and local history. Performed in October 2019, the Putney Hill Cemetery Walk is a theatrical production designed to entertain and educate attendees about people buried in, or excluded from, the town’s earliest cemetery. Written by Lynn Clark, the script deconstructs the traditional narratives of conflict, racism and misogyny and instead constructs an inclusive, multi-vocal narrative of Hopkinton past and present. Volunteers carried out extensive research, and under the direction of Beth Spaulding, local actors vividly brought to life 26 of Hopkinton’s former residents. Audience members were appreciative of the historical context and multiple perspectives about issues that people are grappling with today, noting that issues from 250 years ago, such as religious freedom, voting rights, settler colonialism, racism and women’s rights, have their parallels today. The Putney Hill Cemetery Walk is the seventh Cemetery Walk produced by the Hopkinton Historical Society. DVD copies are available at the Society. This year, AASLH is proud to confer fifty-seven national awards honoring people, projects, exhibits, and publications. The winners represent the best in the field and provide leadership for the future of state and local history. “Very seldom have we seen our village so quiet for many days and weeks. Little is being done but care for the sick and gather crops.” Kearsarge Independent & Times, October 11, 1918

1918 Influenza Pandemic in Hopkinton, NH Photograph of Etta Lucy Bohanan Nelson and her daughter Margery. Etta was one of 13 victims of the influenza pandemic in Hopkinton. She died October 18, 1918.

The 1918 influenza pandemic was unlike any other. Originally known as the Spanish flu, it is now thought to have originated in the United States. Starting as any other flu virus, it mutated into a highly virulent “super-virus” that targeted young adults in their prime and spread easily especially in crowded quarters such as military training camps, college dormitories, schools, and social gatherings. Once contracted, it progressed quickly and violently, causing extremely intense head and body aches, internal bleeding, changes in skin coloration, and rapid deterioration of the lungs; within four to seven days, the victim could be dead or on a slow path to recovery. Globally, it is estimated this pandemic caused 20 to 50 million deaths; a large percentage of these were young adults in their twenties and thirties. Present in 1917, the pandemic reached its peak of destruction in the United States from mid-September to early December, 1918. Like many towns, Hopkinton folks did not immediately recognize the seriousness of the pandemic. The first death in town was George Conant, a bright and popular recent high school graduate. His body was returned to Contoocook for his funeral one week after departing for Dartmouth College, having died on September 22, 1918. In fact, even his family members assumed his illness occurred as the result of sleeping on a rain-soaked mattress, not the pandemic influenza. It took another week for people to take precautions; in the meantime, the Hopkinton Fair, with some 4,000 attendees, did not seem to be affected. By the end of the first week of October, the local newspaper reported “there are 70 cases of influenza in town, and many of them very severe, but at this writing, none have proved fatal. How thankful we are for our capable physicians.” In reality, four Hopkinton deaths had occurred by October 6th and five more would occur in October. The drug store advertised Sunday hours, 8-10 am and 12-1 pm, beginning after October 1st. Hopkinton schools were closed week by week for the month of October, with hope in each announcement that reopening would be possible the following week. Meetings of the Grange and Rebekahs were cancelled. As stated in the Kearsarge Independent and Times newspaper on October 11th, “Very seldom have we seen our village so quiet for many days and weeks. Little is being done but care for the sick and gather crops.” By November 1st, schools had reopened and there was a sense of relief that the worst had passed. With the end of WWI, the spirits of all were high. A peace rally occurred in mid-November and the whole town enthusiastically participated, with bells and whistles early in the morning, celebrations all day long, and a huge parade and Kaiser effigy burning in the evening. Still there were more deaths from influenza, one in early November, one in December, and two at the beginning of January, including the death of the high school principal, Wesley Eastman. The profile of the pandemic in Hopkinton mirrored that of the United States as a whole. The majority of deaths had occurred in late September through early November (10 of 13) and had taken adults ages 35 and under (10 of 13). The care of those who were ill, however, differed from that of many towns and cities. Even in Concord, hospitalization and congregate care were common, but in Hopkinton, doctors and local caregivers went to the patients’ homes. This likely may have prevented a larger number of deaths in Hopkinton. As a result of the 1918 influenza pandemic and new requirements of the State Board of Education, Hopkinton schools made several changes to promote good health:

George Elmer Conant, age 17, September 22, 1918: “One of the most promising and popular young men in town” and having been accepted at Dartmouth College, he left home on Tuesday for Hanover, took sick Thursday, was hospitalized Friday, died Sunday, and was honored with a funeral of very large attendance on the following Tuesday. George William Marsh, age 63, September 27, 1918: Having labored at many jobs throughout his life, George and his equally hard-working wife Ella had finally gained financial stability and home ownership with a mortgage which was lost upon his death; Ella at age 67 became a live-in servant to an older man. Clarence Lorenzo Tilton, age 28, October 3, 1918: A recently divorced father with day-to-day responsibility for two young children, Clarence, a resident of Webster, was being cared for in Contoocook when he died. Birge Lester Fenton, age 29, October 6, 1918: Unmarried and a fireman for the B & M Railroad in Concord, Birge was active in the Order of United American Mechanics, the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen and Enginemen, and the Loyal Order of the Moose, each represented at his funeral. Mildred Lillian Jordan White, age 20, October 8, 1918: Mildred died while trying to care for her three little children, ages 4, almost 3, and 10 months, her husband being out with a lumber crew in the Hatfield area. Mildred had been caring for another young woman with influenza who also died, as did Mildred’s two youngest. Howard Adams, age 23, October 13, 1918: Howard lived with his mother and step-father, Laura and Frank Fifield, in Contoocook, worked in the local silk and saw mills, and was a member of the Free Baptist Church. He was a person of fragile health, exempted from the draft due to “ill health.” The Kearsarge Independent & Times newspaper reported him to be very sick with influenza for over a week and being cared for by Mrs. J. A. Sherwan, evidently one of a number of caregivers who attended very ill townspeople in their homes. Jane Magnan, age 86, October 15, 1918: The oldest pandemic victim in Hopkinton, Jane appears to have had a full life with a long first marriage and two more marriages later in life; her controversial will left her property to her third very young husband and to a very long-time boarder. Herman Scott Spoffard, age 35, October 15, 1918: Born and raised on a farm in Hopkinton, Herman became a miller of grain, saved his money, and bought a milk route in Concord. In support of the Great War, he put many extra hours into crop production while continuing milk production and also purchased war bonds being quoted in his obituary, “Certainly, I can at least do that much.” He may have been only the second of these Hopkinton thirteen who died in a hospital. Etta Lucy Bohanan Nelson, age 34, October 18, 1918: Married for fourteen years and with two children, Margery, 6, and Stanley, 1, both Etta and her husband Eddie, in the prime of life, became so severely ill with the influenza that neither was expected to survive. Eddie finally recovered and raised the two children with the help of his mother-in-law, Delia Bohanan. Eugene Andrew Tallant, age 33, November 4, 1918: One of 15 children raised on a farm in Pelham, Eugene came to Hopkinton, working as a farmer and a lumberman. His obituary noted, “Gene was industrious, and on account of his unusually strong physique and jovial nature was well known about his town.” He had been married five years and was without children at the time of his death. His wife Emma never remarried and eventually became a nurse. Dwight Eugene Conant, age 46, December 14, 1918: A hard-working, well-respected manager of the Conant Manufacturing Company in Contoocook, a silk mill which had been established by his father, Dwight and his wife Blanche were parents of George, the first local fatality of the pandemic. Though violent illness had spread rapidly through town, theirs was the only family to lose two of its members. Wesley E. Eastman, age 29, January 2, 1919: Raised on a farm in Andover, NH, Wesley had earned his degree at the state college in Durham, gained an advanced degree in Michigan, and taught geology at Michigan Agricultural College before coming to Hopkinton in the fall of 1918 as the new principal of the high school. At the time of his death, he had a 3-year-old son and his wife Elaine was pregnant with a daughter born one month later. Mabel C. Martin, age 19, January 3, 1919: Mabel died at the home of her friend, Jessie Gould, while both were on winter break from Keene Normal School. Mabel had graduated from Henniker High School with high honors and was demonstrating excellence as a student teacher. Her mother had died when Mabel was only 5 years old; her father had boarded her with a family living next door to him. Her loss was deeply felt by her community. Allita Paine 20 March 2020 update of original from 2017

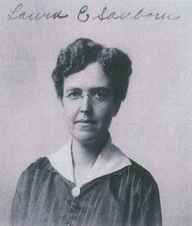

Notable Women of Hopkinton:

Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the Ratification of the 19th Amendment In honor of the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote, Hopkinton Historical Society is recognizing some of the women of Hopkinton whose accomplishments – both large and small – deserve to be highlighted. Their bravery, ingenuity, intelligence, and tenacity is inspiring and we thank them for their contributions. Laura Emily Sanborn World War One Army Nurse Corp. Served June 28, 1917-April 27, 1919 Born February 5, 1881 in Webster, Merrimack County, New Hampshire, Laura Sanborn was the eldest daughter of Charles F. Sanborn and Jennie E. (Colby) Sanborn. Charles F. Sanborn was a farmer and a descendant of Captain Peter Coffin, soldier of the American Revolution. Not much is known about Laura’s early life. She was raised on her father’s farm in Webster along with her siblings, John, Scott, and Annie. In the 1900 United States Federal Census, Laura was 19 years old and single. There is no notation as to her occupation. Between 1900 and 1910, Laura left the family farm in Webster and went to Boston to study nursing at Massachusetts General Hospital. In 1910, Laura was employed as a private nurse in the home of Anna Wright, a widow. Laura was one of seven employees living in Mrs. Wright’s home on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston. A small item in The Kearsarge Times, dated 16 February 1917, noted, “Miss Laura Sanborn, trained nurse of Boston has been spending some time here at the home of her father, Charles Sanborn.” The First World War, originating in Europe, began on July 28, 1914. The United States entered the war on 6 April 1917, joining its allies, Britain, France, and Russia. Two months later, on June 23, 1917, Laura signed a United States passport application to travel overseas to France as a nurse. She was enrolled as a Red Cross nurse, sworn into the army, and on July 10, 1917, Laura, along with 63 other nurses, departed New York City sailing on the Aurania to be stationed with Base Hospital No. 6, a medical surgical unit of Massachusetts General Hospital, in Bordeaux, France, where the nurses were known as the “Bordeaux Belles.” Base Hospital No. 6 was well equipped to handle wounded and sick soldiers, including the treatment of soldiers with infectious diseases. By the last months of the war, the hospital ran at capacity with casualties from the Meuse-Argonne offensive, a major part of the final Allied offensive of World War One that was fought for 47 days and is one of the deadliest battles in American history, resulting in over 350,000 casualties, including over 26,000 Americans. Between August of 1917 and September of 1918, the total number of patients treated, both surgically and medically, was 26,156, including 580 allied sick and wounded. It must have been a relief to Laura when the war ended on November 18, 1918. Laura departed from Bordeaux, France on 14 February 1919 on the ship Abengarez to the port of Hoboken, New Jersey, arriving on March 2, 1919. Laura returned home to Contoocook, where her parents and her brother, John, were living on Pine Street. In 1920, Laura was employed as a private nurse and living with her family in Contoocook. In the 1930 United States Federal Census, Laura was living with her mother, Jennie, and her brother, John, on Pine Street. Her occupation was a private nurse however, it was noted on the census form that she was an “unpaid worker, member of the family.” This likely indicates that she was the caretaker for her mother. The 1940 United States Federal Census records that Laura was living alone on Pine Street as the head of household. Her occupation was left blank. Laura never married. She died January 10, 1969 and is buried alongside her family in Contoocook Village Cemetery. Laura’s 1917 passport application describes her as 36 years-old, 5’6” tall, with blue-gray eyes, and medium brown hair. The accompanying passport photo of Laura reflects a woman, half in shadow, staring directly into the camera. She has a kind face and a slight smile on her lips. She appears to be a woman who knows what she is about, where she is going, and what she has to do. One can only imagine the horrors she witnessed taking care of the young men on her watch at Base Hospital No. 6. One can also imagine that, perhaps, while tending to a dying solder, Laura Sanborn’s calm blue-gray eyes were the last vision a young man saw in the Great War. Nadine Ferrero January 24, 2020 |